Goethe, Groddeck, Hafiz, Hüppi

On the first evening of the symposium, Otto Jägersberg invited all the participants to the Alte Dampfbad (Old Steam Bath), where he opened the exhibition of works by Alfonso Hüppi, “Aladdin’s Lamp – The Hafiz Cycle”, with a short speech.

|

|

| © Alfonso Hüppi |

“Aladdin’s Lamp” – is the name Alfonso Hüppi gave to the ceiling lights in a unpretentious mosque which he photographed while on a trip to Iran with students and published in a catalogue.

These lights (there were similar, indeed even more shrill versions in 1950s living-rooms) are to be regarded as symbols of Islamic faith, modest reflections of a hopeful trust that sees in those lamps the reflection of divine light, it says in the West-Eastern Divan.

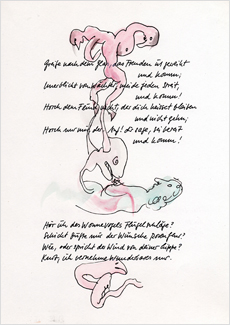

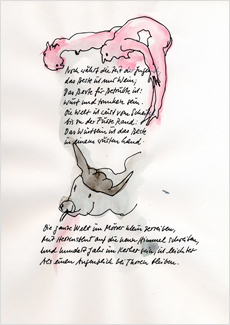

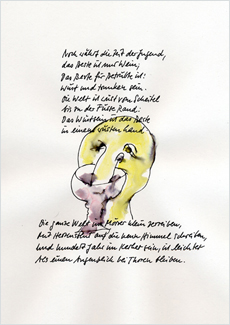

In his Hafiz Cycle “Aladdin’s Lamp” Alfonso Hüppi brings together watercolours and drawings, West and East, in conjunction with texts by Goethe, Hafiz and Nietzsche.

Hüppi has varied the poems and songs from Aladdin’s Lamp in different ways and painted over them. Many of these works clearly illustrate his working motto: Just chance – yes, but intentional!

Goethe and Nietzsche were also great providers of ideas for Groddeck. The term “Gottnatur”, for his lecture series “Hin zu Gottnatur”, he took from Goethe. Groddeck saw the “Gottnatur” as the Es. He mentions this for the first time in 1909 – and in Nietzsche we find the idea that it is wrong to say: I think, we should say instead: it thinks.

Nietzsche is known to have walked from Steinabad near Bonndorf to Rothaus in the Black Forest to drink a few glasses of Rothaus beer. Hafiz & Goethe did not drink beer. Goethe recommended beer for young calves only. Beer was nothing for the mentality of adults, although exceptions were possible for reasons of thirst. Beer inflates thinking and feeling into a yeasty dough and pumps its nutrients into the phlegm. Wine by contrast permeates the intestines and brings the brain’s mental drive to fruition.

|

|

| © Alfonso Hüppi |

Hafiz was called the mystical tongue because of his sublime songs which praised everything earthly and sensual, especially wine, with ascetic enthusiasm. The composition of the songs is free, daring and cheerful, and they also poke fun at priests, monks, mystics and dogmatists. Yet Hafiz himself was a teacher, mystic and Koran interpreter, and belonged to a community of dervishes and Sufis. But he could not have cared less:

Ask not what use

Is drunkenness!

From reason, when you drink,

You are released.

Is drunkenness!

From reason, when you drink,

You are released.

I will drink glass after glass

I will kiss, kiss after kiss,

I will love exceedingly

I will drink endlessly.

I will kiss, kiss after kiss,

I will love exceedingly

I will drink endlessly.

With the frock, it is true,

Our lifestyle is hard to reconcile,

But our soul no longer

Wears the frock.

Our lifestyle is hard to reconcile,

But our soul no longer

Wears the frock.

Bring me the philosopher’s stone,

Bring me the cup of Dchemshid,

The mirror of Alexander

And the seal of Salomon,

Bring me, in a word,

Bring, oh cup-bearer, bring wine!

Bring me the cup of Dchemshid,

The mirror of Alexander

And the seal of Salomon,

Bring me, in a word,

Bring, oh cup-bearer, bring wine!

Wine, to wash the frock,

Stained as it is by pride

And by the black spot of hatred,

Wine, so that I might rupture

With a strengthened arm

The yarn of nonsense

Spread over the world and life

By clerical deception;

Wine, that I might conquer the world;

Wine, that with one leap I might

Jump over both worlds;

Bring, oh cup-bearer, bring wine!

Stained as it is by pride

And by the black spot of hatred,

Wine, so that I might rupture

With a strengthened arm

The yarn of nonsense

Spread over the world and life

By clerical deception;

Wine, that I might conquer the world;

Wine, that with one leap I might

Jump over both worlds;

Bring, oh cup-bearer, bring wine!

How can a committed Mohammedan praise wine in this way? Hafiz says: “Always have the best wine brought, for if the wine is bad, the meal will be regarded as bad. What is more, it is a sin to drink wine. So if you commit a sin, then do so at least with the best wine, for otherwise you would be both committing a sin and drinking bad wine.”

The contradiction between Hafiz’ hymns to wine and the prohibition of wine in the Koran is summed up nicely by Goethe to the extent that he had the prophet forbid the faithful to drink wine so as to keep the privilege to become drunk for himself.

|

|

| © Alfonso Hüppi |

Groddeck, who grew up with wine from Saale and Unstrut, confessed in 1900, when he opened his sanatorium Marienhöhe in Baden-Baden, to drinking Riesling from the Baden-Baden region and making it a medical cure-all.

Goethe describes an identical cure with wine:

When we think soberly

In bad we delight;

When we have drunk a bit

We know what's right;

Yet we exceed the mark

Soon as we do it:

Hafiz, O tell it me,

How did you view it!

In bad we delight;

When we have drunk a bit

We know what's right;

Yet we exceed the mark

Soon as we do it:

Hafiz, O tell it me,

How did you view it!

For my opinion is

Not overblown:

If you can't drink a lot

Leave love alone;

Drinkers their value should

No better think:

If you can't love a lot

You should not drink.

Not overblown:

If you can't drink a lot

Leave love alone;

Drinkers their value should

No better think:

If you can't love a lot

You should not drink.

Goethe did not know the East, he never travelled there. In summer 1814, when he first laid hands on a volume of Hafiz, he experienced a production drive as in his youth. The Peace of Paris had just been signed, Germany was free of the clamour of war, people could travel again – Hafiz came at just the right moment to celebrate this new joie de vivre. Goethe saw himself as a traveller in the Orient (Goethe as precursor of Karl May), delighting in its habits and customs, its religious spirit and disposition, indeed he felt he was a Muslim:

“To understand poetry you must go to the land of poems / to understand the poet you must go to the land of the poet.”

The participants in the Groddeck Symposium can make use of this motto on Sunday at 11 am by visiting the Marienhöhe, Groddeck’s house on Hans-Thomas-Straße and the Es Punkt in the Lichtenthal Woods.

Goethe wrote to Zelter: “Meantime new poems are accumulating for the Divan. This Mohammedan religion, this mythology, these customs, provide scope for a poetry that befits my years. Unconditional surrender to the unfathomable will of God, cheerful overview of the hustle and bustle on earth, ever changing, ever returning in circles and spirals, love, inclination, hovering between two worlds, everything real purified, symbolically dissolving. What more could a granddad want?“

That you can never end, that makes you great,

That you cannot begin, that is your fate.

Your song revolves as vaulted constellations.

End and beginning are re-iterations,

The import of the middle clear akin

To that which ends and as it did begin.

That you cannot begin, that is your fate.

Your song revolves as vaulted constellations.

End and beginning are re-iterations,

The import of the middle clear akin

To that which ends and as it did begin.

In you true source of joy and poetry shows,

From you unnumbered wave on wave outflows.

A mouth that's ready for the kiss,

Full-breasted voice which sweetness fills,

A throat which drink can never miss,

Good heart which always over-spills.

From you unnumbered wave on wave outflows.

A mouth that's ready for the kiss,

Full-breasted voice which sweetness fills,

A throat which drink can never miss,

Good heart which always over-spills.

And let the world entirely sink!

Hafiz, with you or else with none

I will compete! Let joy and pain

Be ours, as twins, in common!

Like you to love and so to drink,

My pride, my life shall this sustain.

Hafiz, with you or else with none

I will compete! Let joy and pain

Be ours, as twins, in common!

Like you to love and so to drink,

My pride, my life shall this sustain.

Goethe celebrates the encounter with Hafiz, and in doing so adopts his style; his poem is itself Hafiz-like: motifs without beginning or end, full of allusions, no strict composition, as is appropriate to the East.

Drunken, all must to this incline!

Youth is drunkenness less the wine;

Age may its youth in drinking renew,

Wonderful virtue so to do.

Youth is drunkenness less the wine;

Age may its youth in drinking renew,

Wonderful virtue so to do.

|

|

| © Alfonso Hüppi |

That was after the Divan was published. During the time when she was still co-author, and in that state in which she was a puzzle to herself, she stayed for a while here, behind the Old Steam Bath in the New Castle, in a meantime demolished little tower, and invited Goethe to visit her.

Goethe set out immediately, but after only a few kilometres one of the coach wheels broke. For Goethe this was a bad omen – he turned back. Goethe never got as far as Baden-Baden. This is a fact we simply have to live with …